Get ready to start considering Blade Runner even more jaw-droppingly detailed and perfect than you already think it is. And believe it or not, Edward James Olmos gets all possible credit for this one.

Get ready to start considering Blade Runner even more jaw-droppingly detailed and perfect than you already think it is. And believe it or not, Edward James Olmos gets all possible credit for this one.Reportedly among the most diligent workers on director Ridley Scott's Blade Runner set, Olmos himself came up with the Cityspeak language—a mixture of Spanish, French, Chinese, German, Hungarian, and Japanese—that is spoken primarily by Gaff, the origami-slinging, workaday blade runner who tails the older, crustier blade runner Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) throughout the story. Cityspeak intensifies and shades the Gaff character, who does much in little screen time. But Cityspeak also allows for a gorgeously complex moment, one I've never seen discussed elsewhere, that ends up forging an extremely sneaky bond between the film and its true father: sci-fi novelist Philip K. Dick. Unless you've been living on Pluto for the last 20 years, I don't have to tell you that Philip K. Dick wrote Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the 1968 novel upon which Blade Runner was loosely based.

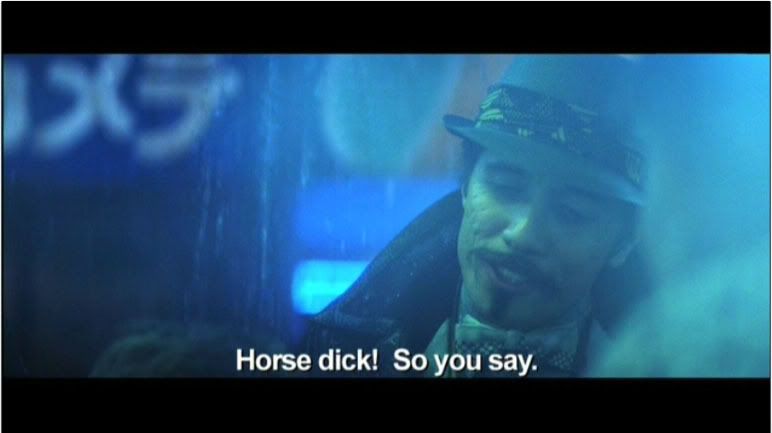

Early in the film, we are sitting inside the White Dragon Noodle Bar. Gaff approaches Deckard mid-noodle, to inform him that police captain Bryant needs him back on yet another blade-running case, like ASAP. Deckard's eating but he's not biting, telling Gaff "You got the wrong guy, pal!" Gaff's response is sharp and extremely Hungarian: "Lófaszt, nehogy már. Te vagy a Blade ... Blade Runner." The authoritative documentary Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner, included with a recent special edition of Blade Runner: The Final Cut, offers this stunning translation of Gaff's first sentence:

That's right. Gaff calls Deckard "horse dick." And here's the part where Philip K. Dick nerds start to maybe glimpse the 100%-mind-blowing place I'm going with all this.

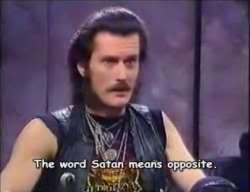

See, in 1981, Philip K. Dick published a really great novel called VALIS. The main character in VALIS is a guy named Horselover Fat. Weird name, right? I thought so too. But let's cautiously march ahead and quote wikipedia: "Even though the book is written in the first-person-autobiographical, for most of the book Dick treats himself and [Horselover] Fat as two separate characters; he describes conversations and arguments with Fat, and harshly if sympathetically criticizes his opinions and writings." Over the course of the book, it becomes clear that Horselover Fat and Philip K. Dick are two versions of the same guy—or, to put it simply, Horselover Fat is an author surrogate for Philip K. Dick.

It's right there in his name, in fact. As VALIS eventually spells out, "Horselover" is English for the Greek word philippos, meaning "lover of horses," while "Fat" is the English translation of "dick," the German word for "fat." See how Horselover Fat = Philip Dick?

Was Olmos channeling P. K. Dick's identity crisis? Did he just happen to be reading the freshly published VALIS? I really doubt both. But during principal photography in 1981, what Hungarian epithet—of all the Hungarian epithets he could've chosen—did Edward James Olmos just so happen to sling at Harrison Ford on the set of Blade Runner, a film based on a Philip K. Dick novel?

"Lófaszt!"..."Horse Dick!"

Folks, it's finally official. Deckard is a replicant. But he's a replicant of Philip K. Dick. Gaff uses Cityspeak to call him as much.

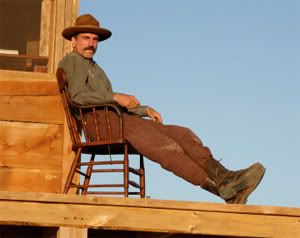

And we all understand by now that Gaff is a guy who would know, don't we?